This hike is considered by many outdoorsmen to be Utahís

premier canyoneering experience-especially if it is done as a one-way hike

from the Wildcat Canyon Trailhead (see page 399). The route from Wildcat

Canyon is more technical than the hike up Left Fork Creek described below,

but either approach will take you to the section of canyon commonly referred

to as the Subway. The canyon narrows that comprise the Subway are actually

only 400 yards long, but the scenery within that short section of canyon is

truly spectacular. Many of the photographic prints for sale in Southern

Utah's art galleries were taken there, and if you are a landscape

photographer the Subway should be high on your list of places to see.

From the Left Fork Trailhead an excellent trail sets off

in a northeasterly direction through the pinion and juniper trees toward the

south side of Tabernacle Dome. The path crosses a shallow drainage after 5

minutes, then continues on for another 0.4 mile to the northern rim of Great

West Canyon. The canyon is 400 feet deep at this point, and from the rim you

can clearly see the trail snaking its way down the side to meet the Left

Fork of North Creek at the bottom. Water can always be found in Left Fork so

it is not necessary to carry a great deal of water on this hike, but it must

be filtered or treated before drinking.

Once on the canyon floor the route follows the stream all

the way to the Subway. There is a reasonable trail much of the way, but it

occasionally fades away or gets lost in the rocky areas, so be prepared to

do some scrambling and bushwhacking. Also, donít hesitate to cross the

stream from time to time in search of the easiest route. Often the easiest

route is in the stream itself.

0.5 mile upstream from the point where the trail first

meets the canyon bottom you will see a break in the north canyon wall where

Pine Spring Wash flows into the Left Fork. Unfortunately, however, the main

trail is on the south side of Left Fork at this point so you will probably

not see the water rushing down from Pine Spring. A short distance further

upstream Little Creek also flows into the north side of Left Fork, but the

trail does not cross to the north side of the canyon floor until it is above

the Little Creek confluence.

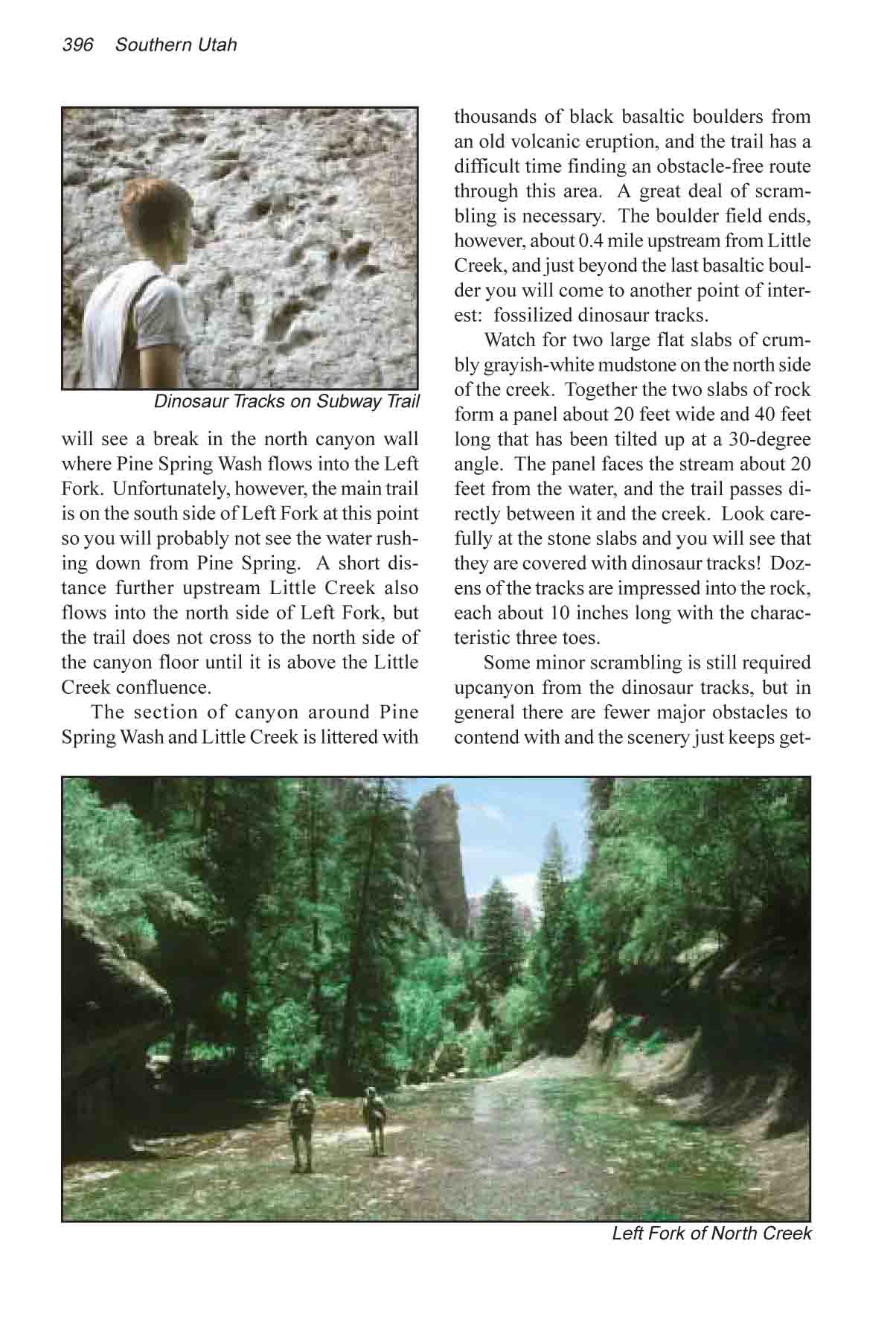

The section of canyon around Pine Spring Wash and Little

Creek is littered with thousands of black basaltic boulders from an old

volcanic eruption, and the trail has a difficult time finding an

obstacle-free route through this area. A great deal of scrambling is

necessary. The boulder field ends, however, about 0.4 mile upstream from

Little Creek, and just beyond the last basaltic boulder you will come to

another point of interest: fossilized dinosaur tracks.

Watch for two large flat slabs of crumbly grayish-white

mudstone on the north side of the creek. Together the two slabs of rock form

a panel about 20 feet wide and 40 feet long that has been tilted up at a

30-degree angle. The panel faces the stream about 20 feet from the water,

and the trail passes directly between it and the creek. Look carefully at

the stone slabs and you will see that they are covered with dinosaur tracks!

Dozens of the tracks are impressed into the rock, each about 10 inches long

with the characteristic three toes.

Some minor scrambling is still required upcanyon from the

dinosaur tracks, but in general there are fewer major obstacles to contend

with and the scenery just keeps getting better. Occasional outcroppings of

shale in this area form low stairsteps in the streambed, and the creek flows

through a series of delightful cascades as it tumbles down the barriers.

These cascades are particularly impressive over the last mile of this hike

where the creek cuts through the boundary separating the Navajo Sandstone

from the underlying Kayenta Formation.

Finally, 3.0 miles upstream from the point where the

trail first meets Left Fork Creek, you will come to a place where the canyon

floor is paved with a 100-foot-wide sheet of gently sloping slickrock. The

smooth sandstone is covered with a carpet of moss that is kept green and

alive by a thin veneer of water trickling down the slope. The route follows

the wet shimmering slickrock for a distance of several hundred feet, then

bends 90 degrees to the right to enter the section of the canyon known as

the Subway.

At this point there is no mistaking the scene before you.

The famous keyhole-shaped entrance to the Subway lies 200 feet ahead. There

are many photographs of this odd formation in the Zion Visitor Center, and

it will be instantly recognizable to many hikers. The symmetrical opening is

40 feet wide at the bottom with a 10-foot slot in the topóa natural subway

tunnel without the train or the tracks.

As you proceed into the Subway you will notice a string

of potholes that have been dissolved from the sandstone by the unceasing

presence of water. The liquid-filled voids are up to 10 feet in diameter and

5 feet deep, and are arranged along the slickrock floor like a string of

watery glass beads.

200 feet beyond the keyhole formation the streambed

enters a deep meandering channel that ends a short distance later at the

base of a 15-foot waterfall. There is more to see above the waterfall in the

upper Subway, but unfortunately it is nearly impossible to climb above the

waterfall without help. For most people this will be the end of the hike.

With a little advanced planning, however, there still might be a way to get

into the upper Subway.

During the summer months you can usually count on meeting

several groups of hikers that have descended into the Subway from the top of

the Kolob Plateau, a more difficult route that requires some swimming and

rope handling skills. These groups typically reach the upper Subway around

noon or shortly after, and if you happen to be below the waterfall when one

of them arrives the chances are good that you will find a friend willing to

help you up. If you leave the Left Fork Trailhead by 8:00 a.m. you should

have plenty of time to enjoy the scenery and still make it to the Subway

before all of the climbers have descended below the waterfall.

The other requirement is that you carry at least 30 feet

of rope or nylon webbing in your pack. Then all you need to do is throw the

rope up to a person at the top and ask him to tie it onto something for you

before he comes down. Most people climb into the upper Subway from a point

100 feet downstream from the waterfall. There you will find a 60-degree

pitch of slickrock with a permanent belay point bolted into the sandstone at

the top. The pitch is only 30 feet long, and once a rope has been tied or

passed through the belay point it is relatively easy to walk hand-over-hand

up the slickrock. There is a 6-foot vertical section at the bottom of the

pitch that presents a problem for some people, but if you lean back against

the rope and walk up rather than trying to pull yourself up the ascent isnít

too difficult.

If your rope is only 30 feet long you will have to tie

one end to the belay point and abandon it when you climb back down. If your

rope is 60 feet long, however, you can pass it through the belay point

without a knot and then pull it down after you when you return to the bottom

of the pitch. One other hint: it is easier to climb hand-over-hand with wide

nylon webbing than with rope.

If you happen to get stranded above the waterfall without

a rope donít despair. There is another way down. There is a place a few

feet downstream from the waterfall where you can easily slide down a 4 feet

drop into the icy water below. If you donít have a rope but you are with

one or two friends that can give you a boost, you may also be able to get up

to the upper Subway from there.

After climbing the pitch just described you must cross

the top of the waterfall to the left side of the stream, and then continue

on into the upper Subway. You will soon enter a part of the canyon very

different from your earlier experience. Gone are the photogenic pools of

clear water and the moss-covered flowstone. Instead you will enter a dark,

foreboding place with no plant life and almost no sunshine. There is no way

out of the narrow prison-like vault except the way you came in. The walls of

sheer sandstone are overhung and stained with long purplish- black streaks

of desert varnish. Occasional flash floods assure that nothing grows in the

cavern-like narrows. The streambed is scoured clean and any plant that might

try to gain a foothold will eventually be washed away.

The upper Subway is a particularly eerie place to be in

alone. The first time I was there my thoughts were equally divided between

studying the marvels of nature and wondering what it would be like to be

locked in a dungeon. My concerns were real enough that I took the time to

walk back and pull up my rope for fear that some prankster might come into

the lower Subway and pull it down. The canyon twists and turns several times

and finally ends 200 yards later at the base of Keyhole Falls, another small

waterfall. This time there is no way to continue.

Wildcat Canyon Trailhead

The hike described above is the easiest way to see the Subway; however

if you are the adventurous type you might prefer to begin this hike at the

Wildcat Canyon Trailhead. From there it is possible to drop down into the

Subway from above and follow Left Fork Creek back to the road. The Wildcat

Canyon Trailhead is also located on the Kolob Reservoir Road but it is 7.9

miles north of the Left Fork Trailhead, so if you chose to start at Wildcat

Canyon you will need a shuttle car.

Unlike the trail up Left Fork, the route down from the

Wildcat Canyon Trailhead to the Subway has several technical challenges.

Short rappels are required in two places, so you will need some rope

handling skills and a 60-foot length of nylon webbing or rope. You will also

be required to swim across at least two small pools of water, so it is wise

to carry a river bag for your gear. Finally, do not attempt this hike unless

the weather is warm and sunny. The water is always cold and unless you wear

a wet suit there is no way to stay dry.

From the trailhead the Wildcat Canyon Trail heads off in

an easterly direction across the Kolob Plateau for 1.0 mile before arriving

at the Hop Valley Trail junction. Bear left there and continue another 0.2

mile through an open forest of Ponderosa Pine to a second junction where you

must turn right onto the Northgate Peaks Trail. After walking south for just

100 yards on the Northgate Peaks Trail you will see another trail departing

on the left next to a sign marking the route to the Subway.

Up to this point the terrain is relatively flat, but soon

after leaving the Northgate Peaks Trail the path veers to the east and

begins dropping down a long sloping expanse of slickrock into Russell Gulch.

Gone is the sandy trail, but you will have no trouble following the route.

Many people before you have come this way, and the trail is well marked with

stone cairns.

After dropping off the rim into Russell Gulch the trail

meanders southward through the depression for 2.3 miles before finally

arriving at the confluence of Russell Gulch and Left Fork. In order to

continue you must climb down to the canyon floor at this point and turn

right into Left Fork Canyon. Unfortunately, as the trail nears the

confluence it is 150 feet above the streambed, and there appears to be no

easy way to get to the bottom of the sheer canyon walls. If you carefully

follow the cairns, however, they will lead you to a narrow cleft in the

sandstone cliff where there is a feasible route down to the canyon floor.

Once you reach the bottom of Russell Gulch continue south for another 60

yards to the confluence and then turn right into Left Fork Canyon.

The next 1.1 miles below the confluence of Russell Gulch

and Left Fork presents a series of watery challenges that increase in

difficulty as you penetrate deeper into the canyon. At first the obstacles

are nothing more than small water-filled potholes that can usually be

skirted without getting wet. But soon the canyon begins to narrow, and after

about 15 minutes you will come to a 30-foot-long pool of cold water that

completely fills the bottom of the gorge. The only way to get across it is

to swim. This is just the first of several more pools you will encounter.

Some of them can be avoided by scrambling around the canyon walls, but it is

often easier to just take the plunge and wade or swim through.

Finally, just before reaching the Subway, you will be

confronted with the last serious obstacle: Keyhole Falls. Keyhole Falls is a

small 10-foot-high waterfall that seems to have been strategically placed

above the east entrance of the Subway for no other reason than to keep

people out. The canyon is only a few feet wide at the top of the waterfall,

and the only way forward is to do a free rappel over the lip of the pouroff.

The drop is not very high and there is a good belay point at the top of the

fall, but the rappel is almost directly under the unceasing flow of icy

water.

When you reach the bottom of Keyhole Falls you will be in

the upper Subway, and the most difficult part of the hike is behind you. As

described above, one more rappel is required to get from the upper Subway to

the lower Subway, but this last pitch is a simple 30-foot drop down a dry

60-degree incline. From there it is an easy walk down Left Fork Creek to the

Left Fork Trailhead.