|

Links to other sites:

Do you have any recent information to add about this trail?

Ordering books & Maps

Free sample copies of Outdoor Magazines

Comments about this site or our book:

|

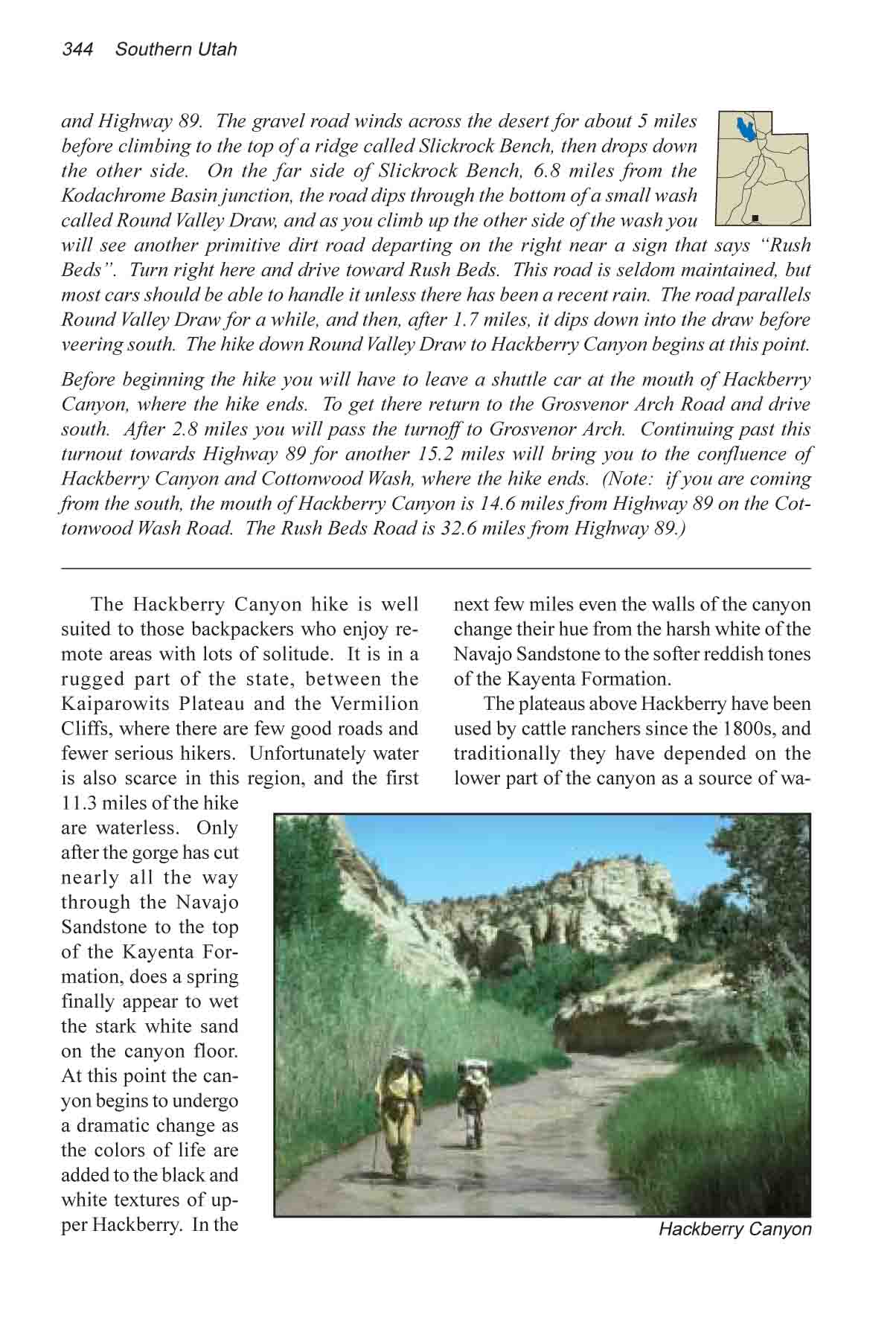

The Hackberry Canyon hike is

well suited to those backpackers who enjoy remote areas with

lots of solitude. It is in a rugged part of the state, between

the Kaiparowits Plateau and the Vermilion Cliffs, where there

are few good roads and fewer serious hikers. Unfortunately water

is also scarce in this region, and the first 11.3 miles of the

hike are waterless. Only after the gorge has cut nearly all the

way through the Navajo Sandstone to the top of the Kayenta Formation,

does a spring finally appear to wet the stark white sand on the

canyon floor. At this point the canyon begins to undergo a dramatic

change as the colors of life are added to the black and white

textures of upper Hackberry. In the next few miles even the walls

of the canyon change their hue from the harsh white of the Navajo

Formation to the softer reddish tones of the Kayenta Sandstone.

The plateaus above Hackberry have

been used by cattle ranchers since the 1800s, and traditionally

they have depended on the lower part of the canyon as a source

of water for their animals. A couple of trails into the canyon

are still occasionally used by local livestockmen, but human

activity is only a fraction of what it was at the turn of the

century.

Day 1

At the trailhead, where Rush Beds

road crosses the top of Round Valley Draw, the draw is very shallow

and uninteresting. The fun begins, however, about 0.5 mile further

down the streambed where, in order to continue, it becomes necessary

to climb down into a 20-foot-deep crack in the bottom of the

gully. The crack is only 12 to 18 inches wide-too narrow to negotiate

with a backpack-so you will have to lower your pack in with a

short rope before climbing down. The narrows continue for about

1.7 more miles before canyon opens up again. In at least three

more places you will meet interesting obstacles that have to

be dealt with. Again, your rope will come in handy for lowering

packs. At one point it will be necessary to crawl through a small

hole under a chock stone; at another your ability to get through

cracks will again be tested.

2.2 miles from the trailhead you

may see a large stone cairn on the north side of the canyon floor.

This marks the beginning of another trail coming down to Round

Valley Draw from Slickrock Bench. Day hikers can exit the draw

at this point and rimwalk back to their car on the Rush Beds

road. The narrows end here and the hike becomes an easy walk

along the dry, sandy streambed. After another 1.0 mile you will

arrive at the confluence with Hackberry Canyon.

Once you reach Hackberry Canyon

turn left and proceed in a southerly direction until you reach

water, 7.8 miles farther down the canyon. You will know you are

getting close when you see a few small cottonwood trees growing

in the sand. Then a short ways farther the sand will turn damp,

and finally you will start to see small pools of water along

the sides of the canyon. At about the point where the water first

starts to flow, 0.6 mile below the first cottonwoods, there is

a good camp site on a sandy knoll on the right side of the canyon.

This site has been used by cowboys for at least a hundred years.

It is also the trailhead for Upper Trail, an old cow trail leading

out of Hackberry Canyon to Death Valley. A short length of barbed

wire fence at the top of the knoll, and a near-vertical cliff

of Navajo Sandstone on the east side of the canyon will help

you identify the site.

Like many of the place names in

the West, there is an interesting story behind how Death Valley

got its name. Cattlemen have long used this valley as a winter

grazing pasture for their cattle. Their are no springs on the

plateau, however, and the cattle depend on Upper Trail for their

access to water. Oldtimers tell the story of how a cow once laid

down and died on a very narrow part of the trail near the rim.

The other cows were not able to get past the dead cow to go down

the trail for water and, as a result, many of them died of thirst

on the plateau above. Since that time the pasture has been known

as Death Valley.

Day 2

As you continue down Hackberry

Canyon from the campsite the water begins to flow a little faster,

but the stream is seldom more than a few inches deep. Dense vegetation

lines the banks, and the easiest place to walk is in the center

of the flat, sandy streambed. Wading shoes are very useful for

the remainder of the hike, as you will be in the water more than

half of the time.

After about ten minutes you will

pass another fence, built across the canyon floor to keep cattle

from wondering downstream, and a mile farther on you will see

Stone Donkey Canyon coming in from the right. Stone Donkey is

a box canyon with no access to the top, but it has nice spring

near its mouth which adds to the meager flow in Hackberry.

1.9 miles below Stone Donkey Canyon

there is a new feature in the canyon that was added in the fall

of 1987. In that year a large rock slide came down from the west

side of Hackberry, creating a dam across the canyon that backed

up the stream for several hundred yards. A number of dead cottonwood

trees reveal the size of the lake that was formed. The lake has

subsided now, however, and it is not difficult to find your way

across the rubble of the slide.

If you are observant you may see

another trail descending into Hackberry Canyon from the west

side a short distance upstream from the rock slide. This is the

Lower Trail, another cow trail leading up to Death Valley. Nearby,

the words “W.M. Chynoweth, 1892” have been scratched

into the canyon wall. The Chynoweths were a prominent ranching

family in southern Utah, and the name appears more than once

in the area’s cowboyglyphs.

The next item of interest is Sam

Pollock Canyon, 1.8 miles below the rock slide. If you have the

time and energy you might want to drop your pack here and make

a side trip into this canyon to see Sam Pollock Natural Arch

(1.6 miles each way). The bottom part of Sam Pollock Canyon is

filled with huge boulders from the cliffs above, and a lot of

scrambling is necessary to get into the canyon. After getting

through a half-mile of sandstone rubble you will be confronted

with a 20-foot vertical pouroff that blocks the upper half of

the canyon, but don’t give up yet. About 200 yards below

the pouroff, on the east side of the canyon there is a relatively

easy way up to a ledge above the pouroff. Once you are on this

ledge you can walk upcanyon on a vague trail to a point just

above the pouroff and then drop 15 feet back down to the streambed.

The route is not difficult at all, but it is a little exposed

at one point so be careful with your footing.

Once above the pouroff it is an

easy 1.1 mile walk up the streambed to the arch, located near

the top of the canyon on the north side. There are also more

cowboyglyphs in the vicinity of Sam Pollock Arch. In a small

cave just north of the arch you can see a glyph scratched into

the rock by another member of the Chynoweth family: “Art

Chynoweth, 1912”.

Continuing down Hackberry Canyon,

be sure not to miss Frank Watson’s cabin. Watson migrated

to Utah from Wisconsin at the turn of the century. Upon his arrival

in Utah he changed his name, for reasons unknown, from Richard

Thomas to Frank Watson, and for the next fifteen years remained

completely out of touch with his relatives in Wisconsin. Many

people came west at that time to begin a new life, and few newcomers

were ever questioned about their past. Watson went to work for

a while in the nearby town of Pahreah (now a ghost town in Paria

Canyon), and in about 1914 he built his cabin in lower Hackberry

Canyon. The cabin is still in surprisingly good shape after all

these years.

The Watson cabin can’t be

seen from Hackberry creek, so it is easy to miss. It is situated

on the edge of a sagebrush-covered bench, some fifteen feet above

the west side of the streambed 0.6 miles downstream from the

mouth of Sam Pollock Canyon. As you walk downstream watch for

a large red sandstone boulder, about 15 feet in diameter, on

the west side of the stream. At the foot of this boulder you

should see a vague trail going up the side of the bank to the

cabin, which is hidden in the sagebrush only 100 feet away.

2.5 miles downstream from Watson’s

cabin Hackberry Canyon makes a sharp turn to the left and knifes

its way through a ridge known as the Cockscomb before converging

with Cottonwood Wash. For the last 1.8 miles the canyon narrows

to twenty or thirty feet, with cliffs of Navajo and Kayenta Sandstone

dropping precipitously from the convoluted Cockscomb to the waters

edge. It is very scenic. Finally Hackberry Creek emerges from

the ridge to join Cottonwood Wash and the road back to Kodachrome

Basin. |