|

Links to other sites:

Do you have any recent information to add about this trail?

Ordering books & Maps

Free sample copies of Outdoor Magazines

Comments about this site or our book:

|

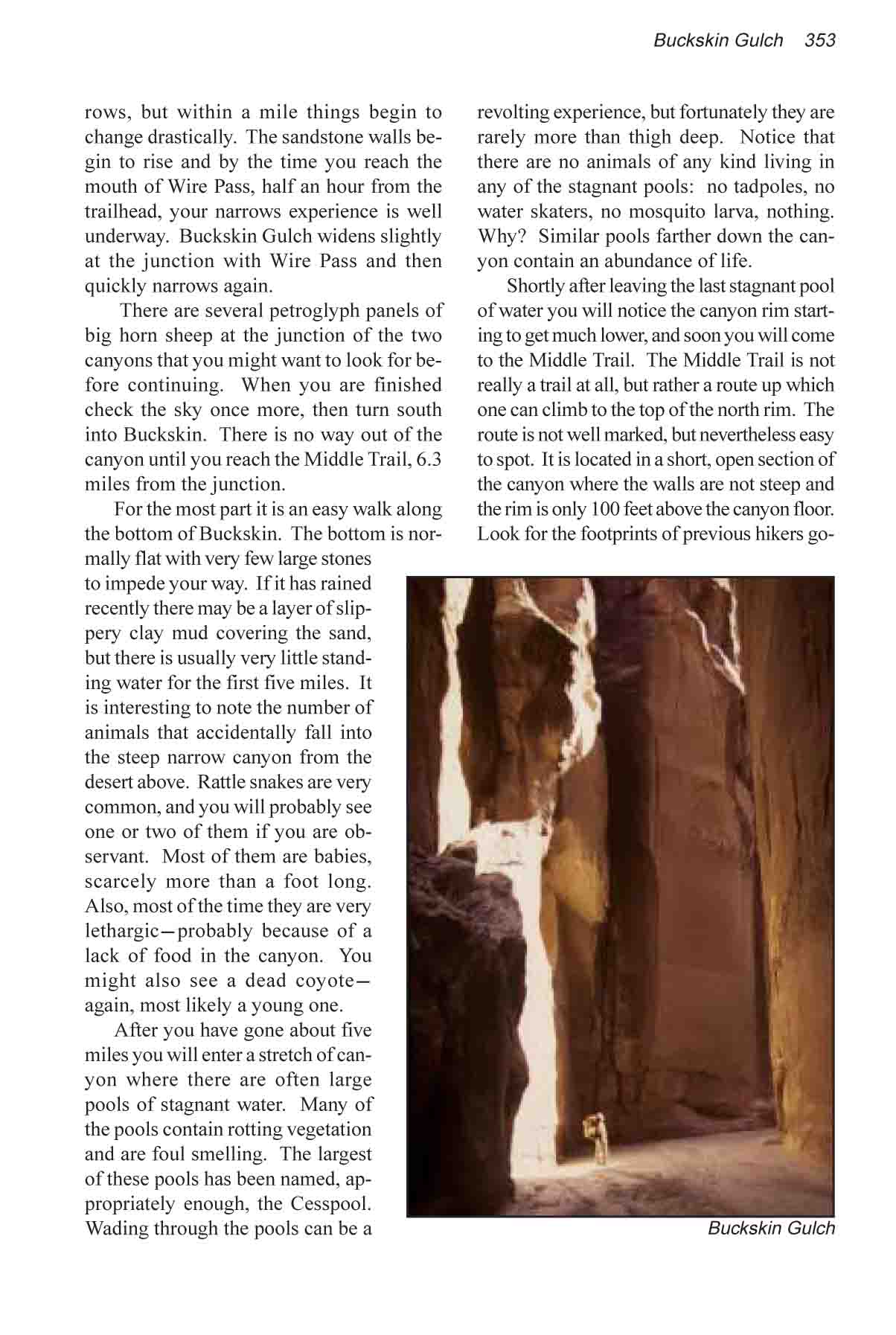

Buckskin Gulch is alleged by

many veteran hikers to be the longest, narrowest slot canyon

in the world. There are many other narrows hikes on the Colorado

Plateau, but Buckskin is exceptional because of its length. The

Buckskin narrows extend almost uninterrupted for over 12 miles

with the width of the canyon seldom exceeding 20 feet. The walk

through the dark, narrow canyon is truly a unique hiking experience.

The key consideration in planning

a trip through Buckskin Gulch is water. How much water and mud

is there in the canyon? And what is the probability that it will

rain while you are inside it? The canyon was created by water,

and water continues to shape it and change its character. As

you walk along the sandy bottom you will continually be confronted

with evidence of previous floods. Dozens of logs have been wedged

between the canyon walls, and piles of huge boulders have been

jammed into narrow constrictions. The characteristics change

from year to year. One can never predict what the last flood

might have taken away or left behind. According to BLM statistics

there are about 8 flash floods a year, on the average, in Paria

Canyon and its tributaries. About a third of the floods occur

during the month of August, so if you are planning a trip in

late summer you should be especially cautious. Flash flood danger

is lowest during the months of April, May, and June.

Day 1

It is possible to begin this hike

at either Buckskin Trailhead or Wire Pass Trailhead, but if you

begin at Buckskin Trailhead the hike is 2.8 miles longer. If

you begin the hike at Wire Pass you will have to walk 13 miles

to the confluence campsite; whereas from Buckskin Trailhead the

distance is 15.8 miles-more than a comfortable day’s walk

for most people.

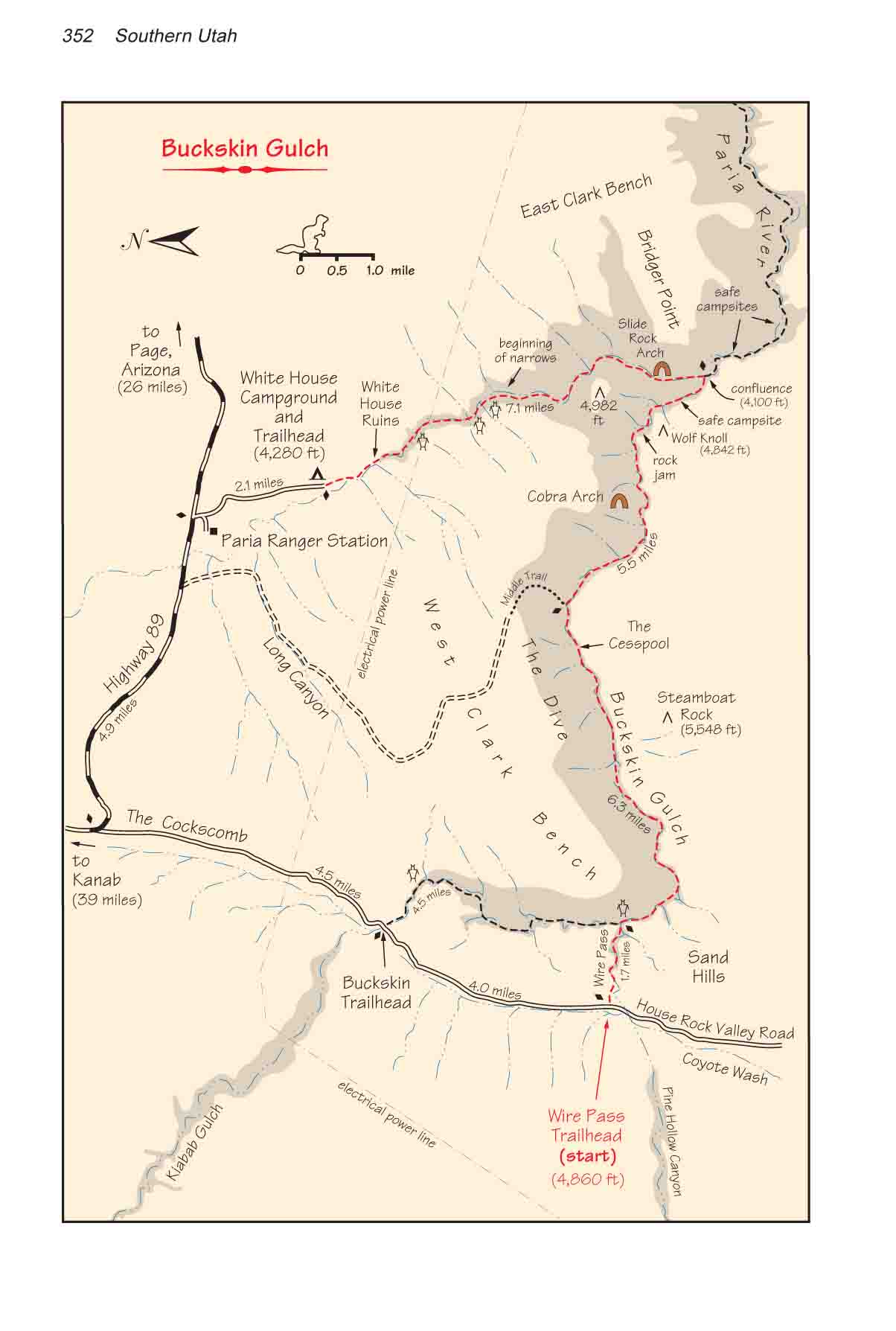

From the Wire Pass parking area

the trail proceeds for a short distance along the south side

of Wire Pass, then drops into the sandy bottom of the wash and

descends eastward through the Cockscomb. At first the wash is

so mundane it hardly seems an appropriate entry point to the

world’s best canyon narrows, but within a mile things begin

to change drastically. The sandstone walls begin to rise and

by the time you reach the mouth of Wire Pass, half an hour from

the trailhead, your narrows experience is well underway. Buckskin

Gulch widens slightly at the junction with Wire Pass and then

quickly narrows again.

There are several petroglyph panels

of big horn sheep at the junction of the two canyons that you

might want to look for before continuing. When you are finished

check the sky once more, then turn south into Buckskin. There

is no way out of the canyon until you reach the Middle Trail,

6.3 miles from the junction.

For the most part it is an easy

walk along the bottom of Buckskin. The bottom is normally flat

with very few large stones to impede your way. If it has rained

recently there may be a layer of slippery clay mud covering the

sand, but there is usually very little standing water for the

first five miles. It is interesting to note the number of animals

that accidentally fall into the steep narrow canyon from the

desert above. Rattle snakes are very common, and you will probably

see one or two of them if you are observant. Most of them are

babies, scarcely more than a foot long. Also, most of the time

they are very lethargic-probably because of a lack of food in

the canyon. You might also see a dead coyote-again, most likely

a young one.

After you have gone about five

miles you will enter a stretch of canyon where there are often

large pools of stagnant water. Many of the pools contain rotting

vegetation and are foul smelling. The largest of these pools

has been named, appropriately enough, the Cesspool. Wading through

the pools can be a revolting experience, but fortunately they

are rarely more than thigh deep. Notice that there are no animals

of any kind living in any of the stagnant pools: no tadpoles,

no water skaters, no mosquito larva, nothing. Why? Similar pools

farther down the canyon contain an abundance of life.

Shortly after leaving the last

stagnant pool of water you will notice the canyon rim starting

to get much lower, and soon you will come to the Middle Trail.

The Middle Trail is not really a trail at all, but rather a route

up which one can climb to the top of the north rim. The route

is not well marked, but nevertheless easy to spot. It is located

in a short, open section of the canyon where the walls are not

steep and the rim is only 100 feet above the canyon floor. Look

for the footprints of previous hikers going into a fault on the

left. The assent is not a walk, but rather a scramble. Hikers

with a modicum of rock climbing skill should have no trouble

getting up, but don’t try it with your backpack on. Better

to leave your pack behind or pull it up after you with a short

piece of rope. With a little route finding skill it is also possible

to climb out to the south rim at this point.

If you got off to a late start

you might want to use the Middle Trail to climb out of the narrows

and make camp for the night. Unfortunately there is nothing but

slickrock and sand above the canyon, and no water. But the flash

flood danger makes it unsafe to spend a night inside Buckskin

Gulch.

Soon after leaving the Middle Trail

the narrows close in again, and the depth of the canyon continues

to increase as you approach the Paria River. There are usually

no more deep wading pools below Middle Trail, but after about

four miles your progress will be stopped by a pile of huge rocks

that have become wedged into a tight constriction in the canyon.

This rock jam is Buckskin Gulch’s most serious obstacle,

and most people will need a rope to get safely around it. The

standard route requires that you climb about 15 feet down the

smooth face of one of the boulders. Previous hikers have chipped

footholds into the soft sandstone, but unless you are very agile

you will still need a rope to make a safe descent. Hikers often

leave their ropes tied to the top of the pitch and you might

be lucky enough to find a good one already in place. But BLM

rangers regularly cut away any ropes that appear to be unsafe,

so you had best have one of your own. Conditions change from

year to year and, depending on what happened during the last

canyon flood, you might find another easier route down the rock

jam. But don’t count on it.

Soon after you leave the rock jam

you will pass by a series of seeps in the Navajo Sandstone walls

that supply a tiny flowing stream on the canyon floor. The fresh

water is a welcome change from the stagnant, lifeless pools above

Middle Trail. There is plenty of life in the water of the lower

Buckskin, even including small fish.

About a mile below the rock jam,

or 0.5 mile above the Paria River confluence, you will come to

an excellent campsite. Look for a large grove of maple and boxelder

trees growing in the sand above the streambed. There are several

fine places to make camp under the trees on the benches of dry

sand ten feet above the canyon floor. Since this area is the

only place in Buckskin Gulch where it is possible to camp you

may have trouble finding an unoccupied campsite, especially during

the busy months of May and June. If you can’t find a place

here the next closest campsite is located about a mile away in

Paria Canyon below the confluence.

Day 2

It is only a ten minute walk from

the Buckskin Gulch campsite to the Paria River confluence, where

you must turn north up Paria Canyon to complete the hike. The

place where the two canyons come together is extremely impressive.

The narrows here are much more open than the narrows of the Buckskin,

but the reddish walls are shear and smooth. The presence of clean

running water at the bottom of the 800-foot gorge also adds a

touch of grandeur to the scene. The Paria is often dry in the

early summer, but there is always at least a trickle of water

flowing out of Buckskin.

The next point of interest as you

walk up the Paria River is Slide Arch, located about 0.7 mile

above the confluence. This is not really an arch at all, but

rather a large piece of sandstone that has broken away from the

east wall and slid down into the river. Beyond Slide Arch the

canyon walls start to become less shear and the canyon widens

until it is eventually little more than a desert wash. There

are a few hard-to-find panels of petroglyphs on the west side

of the canyon as you approach the White House Trailhead. The

first panel is about a mile before the point where the electrical

power lines cross the canyon, and the last is just above the

power line crossing.

Finally, you may want to pause

for a few minutes at the White House Ruins. These are not Indian

ruins, as many people think, but rather the site of an old homesteader’s

cabin. The cabin was originally built in 1887 by Owen Washington

Clark, the same man for whom the West Clark Bench was named.

Unfortunately it burned down in the 1890s, and today there is

little left but a pile of stones. The ruins are located on the

east side of the Paria River, opposite a small side canyon on

the west side about 0.3 mile below the trailhead.

Lower Paria Canyon

Many hikers combine the Buckskin

Gulch hike with a hike through the lower part of Paria Canyon

to the Colorado River. If you turn south at the Paria confluence

instead of north you can walk all the way down the Paria River

to Lees Ferry. This 30-mile walk makes a long but rewarding backpack

trip with a great deal to see. There are several abandoned homestead

sites and mining camps along the way dating back to the late

1800s. You will also see several impressive panels of Indian

rock art, as well as one of the largest natural sandstone arches

in the world. The distance by road from Lees Ferry back to the

Paria Ranger Station is about 70 miles; hence two cars are needed

for the hike. |